What is philatelic literature?

Nearly all collectors keep their stamps in albums or on album leaves. If on these leaves the collector writes say date of issue, or the reason why the stamps were issued, or any other detail, then the page becomes the simplest form of philatelic literature.

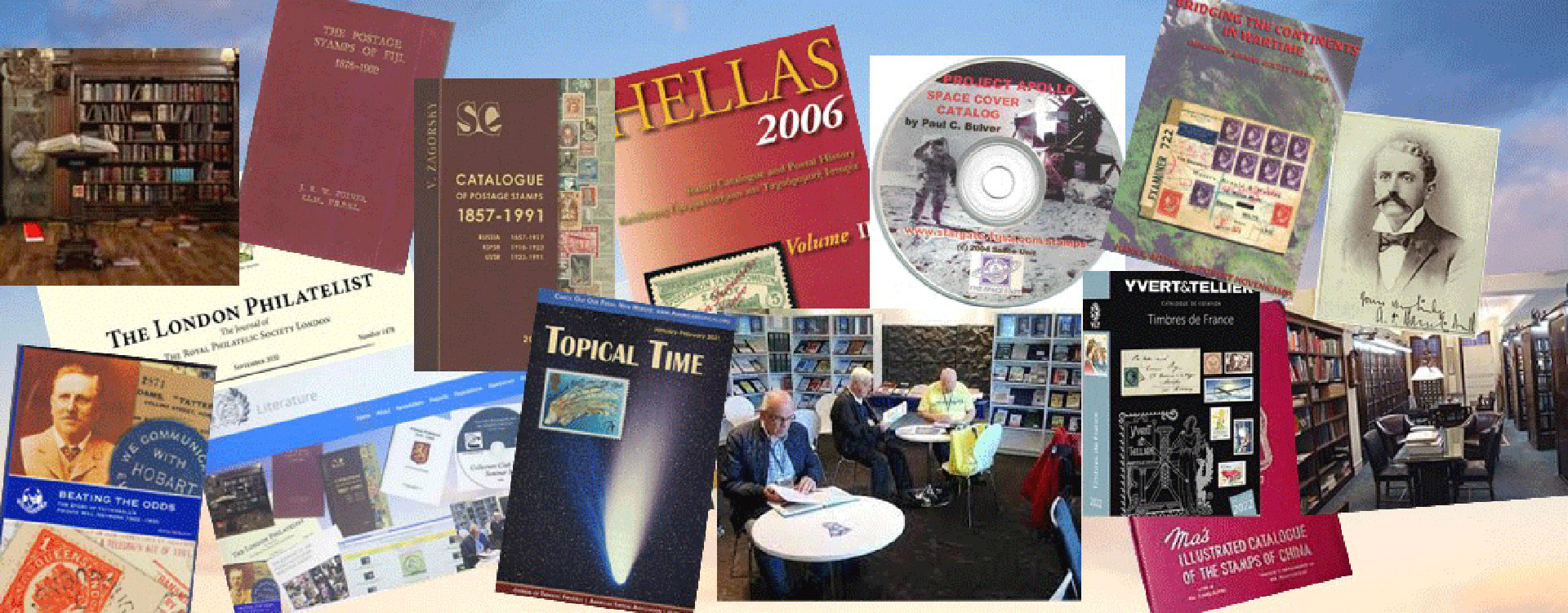

Philatelic Literature is basically the stored form of philatelic knowledge that can be retrieved by other collectors who are interested in information on the same subject. The use of the words ‘stored form’ have been chosen deliberately as with the advent of electronic media, literature can be in the form of manuscript, typed or printed text, magnetic media such as video tapes, electronic media such as on personal computers, or ‘html’ text within a web or internet site. The media used to store philatelic knowledge within philatelic literature is not important other than its usefulness in storage and retrieval. However, more about this later.

Literature is nearly as old as stamp collecting.

James Mackay in “Stamps – Facts and Feats” states that the first collector of postage stamps was Dr JE Gray who purchased a block of Penny Blacks on 1st May 1840, five days before they could be used for the pre-payment of postage. Price lists of stamps, the first form of literature, were published in the 1850s, and the first stamp catalogue was compiled by Alfred Potiquet in 1861. Already by this time we are seeing the important linkage between philately and literature. To put this into perspective, the Royal Philatelic Society London, the oldest philatelic society still in existence, was formed in 1869, and it created a philatelic library in 1887 that nowadays is housed on over 2000 linear metres of shelving, a phenomenal repository of information.

What different forms does literature take? The quick answer is many forms! However, it can be divided into a number of classifications, all of which can be entered into an FIP International Competition. The least complex literature is the popular columns written for daily newspapers. These columns are very important as they are the means of bringing the hobby of philately to the non-collector audience. Leading on from these to more learned writing are the articles that are published in general magazines, stamp magazines or specialist society journals. Considering that the first philatelic periodical was published in 1862 (“Monthly Intelligencer”) the number and scope of articles is enormous. There are within philatelic libraries bibliographies and indexes that assist in finding articles of interest to specific collectors, but they only touch upon a high area of knowledge. Catalogues make up another field of literature – stamp catalogues that grew out of simple price lists and now can be very specialised, and auction catalogues that list philatelic material available by tender sale; the first stamp auction took place in Paris in 1865 and was the stock of a deceased dealer. Catalogues tend to date as more stamps are issued or sold, but even so, often they are an important source of information on what was available on the stamp market at a particular time. The top end of literature is the handbook. Here is found in-depth knowledge on a stamp, a country, a theme etc. It can be traditional philately, postal history, revenues or any other category of philately. Usually handbooks are printed in limited numbers due to the fact that often they are specialised and thus appeal to only a limited number of collectors. Accordingly, many have become rare items with significant intrinsic value. There are a number of dealers who only sell old, or newly published, philatelic handbooks. It is surprising that with the large number of books published, there are still stamp issuing countries that have not had a comprehensive handbook published for over 50 years; Queensland, Ceylon and Leeward Islands are prime examples.

Returning to other forms of literature than the printed word, videos and CD Roms have launched new aspects of philatelic research and knowledge. However, the biggest innovation has been the Internet, or World Wide Web. To give a scale in size of this resource, Joe Luft records on his website nearly 4,000 philatelic websites. The Internet has provided a number of features that can not be achieved easily by the printed word. One main feature is the use of illustrations; there are many sites that provide a picture of collections, album pages, and many, many stamps. The bibliographical aspect of websites have even wider implications to research. For instance, the huge American Philatelic Society’s Library is accessible through the Internet, providing a research tool second to none. There are a number of other sites like this. The importance of the Internet is acknowledged by FIP through its annual ‘website’ competition.

To conclude, it is correct to quote from the FIP Regulations and Guidelines. Philatelic literature includes all communications available to collectors related to postage stamps, postal history, and their collecting, and to any of the specialised fields connected therewith. In many cases, it represents a lifetime of research and effort, which will serve philately for years to come.

Francis Kiddle, RDP, FRPSL

3rd October 2001